We live in an amazing era. Anybody with a sufficient Internet connection, even a wireless connection, can listen to nearly any piece of music they want to.

I vaguely remember a TV commercial from the mid ‘90s, advertising a telecom company by way of advertising the “Information Superhighway”. A weary traveler in a run-down bar in the desert asks the bartender something like “What kind of music you got here?” The bartender answers “Everything.” The traveler asks for a particular recording of a particular piece of classical music, and the bartender immediately puts it on on the cyber-jukebox.

It sounded ludicrous at the time. It’s reality now.

The particular reason I mention this is, I’ve just spent about 8 months listening to the complete works of J. S. Bach, and picking out good recordings of all of them. This wasn’t my intention at the start. At the start I just wanted to discover more good Bach pieces, and put them into a nice deduplicated playlist as I did so. But once you listen to enough Bach, something clicks, and any Bach piece has the potential to be really good. So as the list started filling in and I still wanted to hear even more Bach, I decided to finish the job.

I say “potential” because I found that the recording really matters. For every beautiful, inspired perfomance, there are ten performances that range from dull to tragically bad.

There are a few cases of compositions by Bach where I think nobody has made the right recording yet. But for most of the 1,075-ish pieces in this playlist, I was choosing from multiple great options.

Spotify is the thing that made it possible. Spotify is also the thing that made it hard, because their organization of classical music is so bad. When I was halfway done, I even had the misfortune of upgrading to a version of Spotify that dumbed down the search feature, so searching became much harder until, months later, I learned an undocumented trick that fixes it from the Spotify help forums. (More on this below.)

Spotify needs music librarians. I’m not one, but I’ll play one on the Internet. After all, I’ve just listened to all* Bach’s compositions, and I want to share with you what I found.

The playlists

Let’s get to the point now. Here’s the collection. It’s broken into six playlists to provide a bit of relief to your scrolling fingers. The fact that every* Bach piece is catalogued with a BWV number, and the BWV numbers are approximately sorted by what style of work they are, is quite helpful here. I’ll link to the playlists while describing them in broad strokes:

- BWV 1-249 abridged or unabridged: Big choral works, such as cantatas and masses

- BWV 250-524: Chorales and songs

- BWV 525-770: Organ works

- BWV 772-994: Keyboard works

- BWV 995-1080: Works for orchestras and solo instruments

- BWV 1081-1128: Works discovered since 1950

With these playlists, you could listen to different Bach pieces non-stop for nearly a week.

If you’d prefer a little more focus on quality over quantity — although the quality of things Bach composed is quite high overall — I also made a more-curated list of highlights.

How should you listen?

This is of course really subjective.

My recommendation is to pick a mostly arbitrary point in one of the playlists, but this point should be at the start of a BWV number, or the start of a collection such as the Goldberg Variations. Then listen for a while. When you get to the end of a piece and you want to hear something different, pick a different arbitrary point. Let’s call this “manual shuffle”.

These playlists won’t work well to listen straight through — if you did that, you’d hear all the cantatas first, then all the motets and masses… and you’d get to the instrumental pieces many days later.

In particular, if you listen straight through the BWV 250-524 playlist, you’re gonna have a bad time. You’ll hear a large number of sacred chorales in alphabetical order by their lyrics. It’s like reading a hymnal from start to finish.

Putting all these playlists into a folder and putting the whole folder on shuffle wouldn’t be a terrible thing to do. I wouldn’t entirely recommend it, because you’ll often hear something from the middle of a work out of context that way, but it is at least a convenient way to explore. If you hear a fragment of a work and it interests you, go back and listen to the whole work in order.

The highlights playlist is easier to put on shuffle and slightly better optimized for that purpose. But I still recommend the “manual shuffle” technique most of all for discovering new Bach pieces.

Abridging the recitatives

Why am I suggesting you listen to an “abridged” version of BWV 1-249 in a complete Bach playlist? In that version, I skipped some of the particularly uninteresting recitative movements. Every cantata is in there, but some of them get to the point faster in the abridged list.

It might sound sacrilegious to suggest that Bach wrote some uninteresting movements of cantatas, but he did. I’ve even seen conductors writing program notes who said the same. It’s my opinion that you shouldn’t force yourself to listen to these just because you’re listening to cantatas. Cantatas are an amazing listening experience, an experience you shouldn’t have to delay while listening to someone speak-singing in German on no particular melody just so they can get through all the text.

I think you’d include these recitatives if you actually were performing the music in a church service, as the cantatas originally were, but if you’re just appreciating the music, it’ll work better when some of the recitatives aren’t there.

There are interesting recitatives too, and there are recitatives that are musically important to get from one movement to the next. Those are there in the playlist, even in the abridged version. But you may disagree with my aesthetic choices, and that’s why I included the unabridged 1-249 playlist as well.

Searching for Bach

I’ll restate that trying to find classical music on Spotify is a pretty bad experience overall. There’s just no consistency to how things are labeled. Classical music doesn’t fit in the hierarchy that every major music player has settled on that attempts to describe every track by its “artist”, “album”, and “song”, and some ways that other systems kind of mitigate the problem don’t exist on Spotify.

In classical music, “albums” are unpredictable and arbitrary. They’re not grouped by work, they’re grouped by the whims of the label and by how much music you can fit on a CD. The “artist” is sometimes the composer, but more often the performer, especially when the performance is particularly good (look for the cello suites under “Yo-Yo Ma”, not “J. S. Bach”).

So it would almost sound like there’s no way to search for Bach on Spotify unless you already know what you’re going to find. This is the case for many composers. But in Bach’s case, the BWV catalogue can save the day.

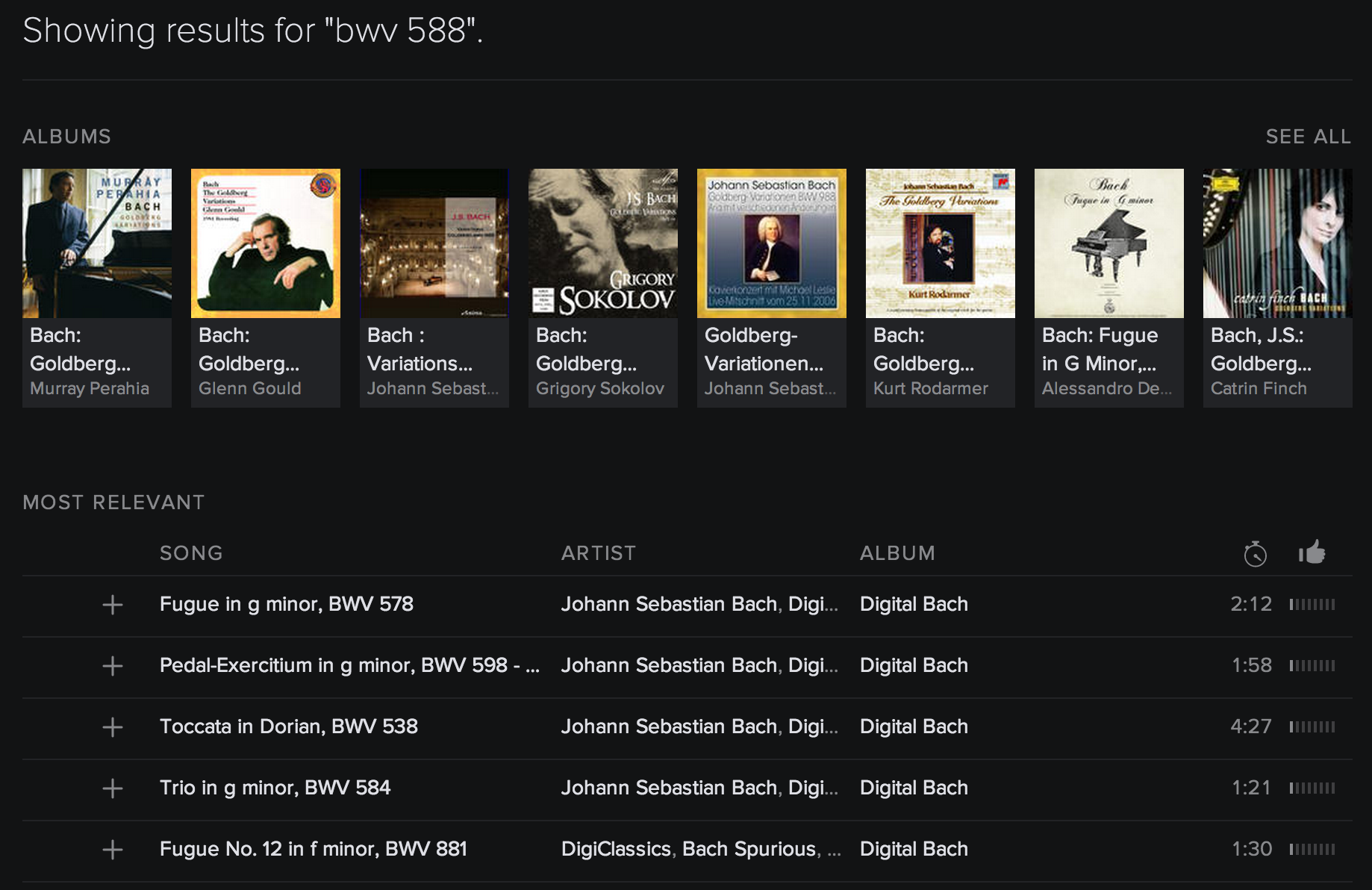

Classical music labels have known for a long time that BWV numbers are the best

way to distinguish which Bach piece is which, so nearly every Bach recording

on Spotify includes the BWV number in its track title. To find all the

recordings of the Canzona in D Minor, BWV 588, you can just type "BWV 588"

in quotes into the search box. Hooray!

No, just kidding. It used to work that way, but now you actually find this:

I really struggle to think of explanations for why the search works this way.

It’s apparently assuming I made a typo. Don’t you hate when you type “588” when you meant “881”? Good thing we have computers to correct us.

It’s correcting me because 588 is a rarely-listened piece, right? It would rather give me more famous pieces like… an organ pedal exercise?

It’s trying to emphasize quality releases like… “Digital Bach”?

If you scroll far enough down in the “Most Relevant” section, past all the not-at-all-relevant things, you’ll find recordings of BWV 588. Particularly the mediocre ones like “Spooky Bach Halloween” by Joe Fox and the Haunted Players.

Finally, at the bottom, you may find the “All Tracks” section — results that Spotify thinks are so irrelevant that they can’t even be on the same list as those titans of relevance we just scrolled past. This is where you might find some good recordings.

Hope you like this organizational scheme, because the results are not sortable. You can’t group them by album or sort them by popularity anymore.

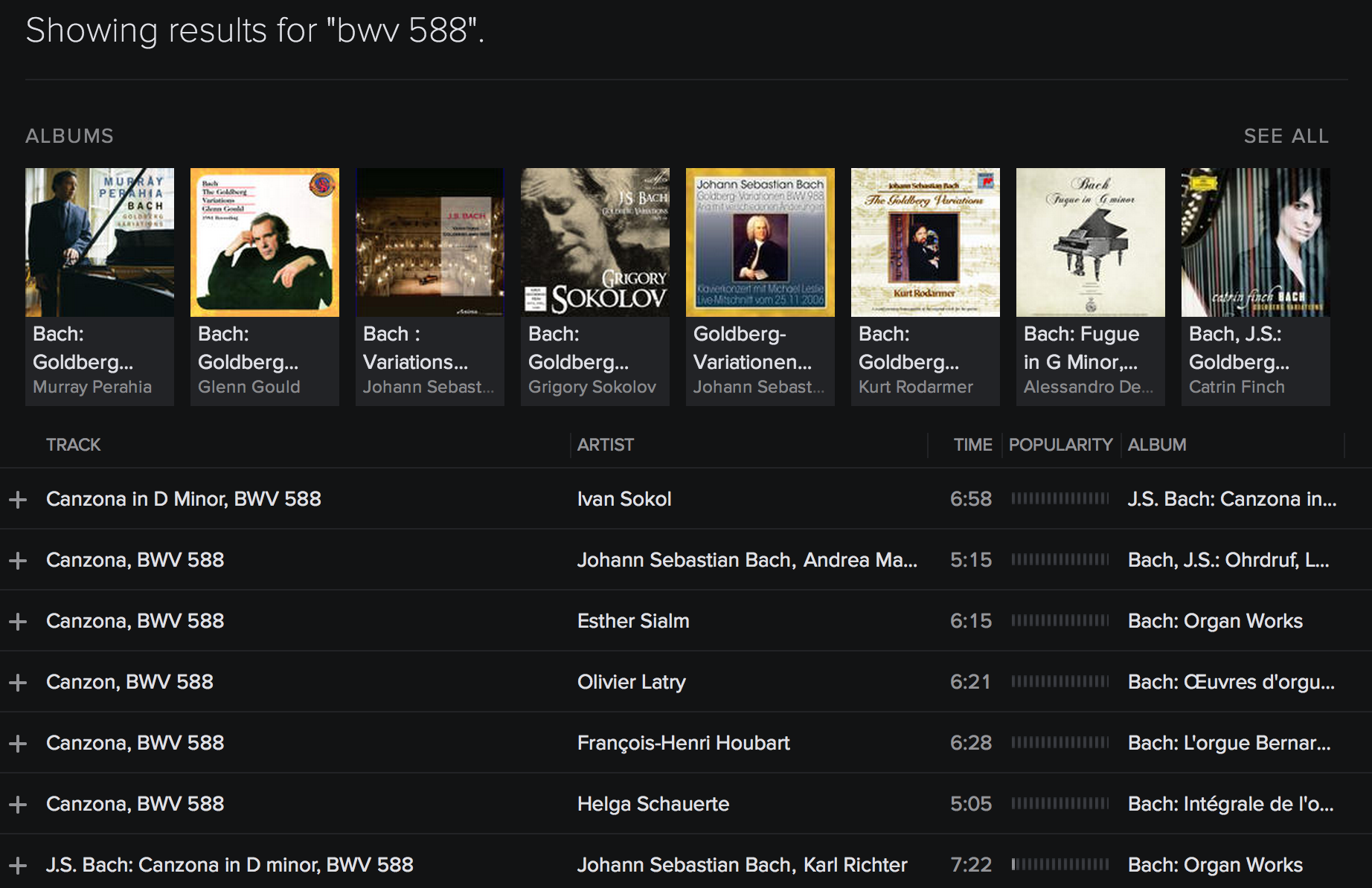

But there’s a trick. A brilliant user named StevenR posted an incantation on the Spotify help forums that gets back the old search behavior. You type this into the search box:

spotify:search:"BWV 588"

This undocumented feature does revolutionary things like giving results that are all the correct piece, with good results near the top, and the columns are adjustable and sortable.

If they ever take this away, the next version of this list might be on Rdio.

Judging albums by their cover

It seems that Bach, more than other composers, has motivated some performers to plod through an uninspired performance just to get a recording out there. The worst offenders are the compilation albums that shovel together generic recordings for some utilitarian purpose, with names like “Bach for Studying”, “Bach To Train Your Brain”, the aforementioned “Spooky Bach Halloween”, and worst of all “Smart Babies”.

Even the ones that sound well-intentioned, such as “Fifty Essential Bach Pieces”, are not going to get you the right recordings. That may sound like a hypocritical thing for me to say when I’m presenting an enormous Bach compilation. But the issue here is that the compilation albums didn’t license the best performances, just the ones that were most convenient to re-release. I can put Glenn Gould on the playlist. They can’t.

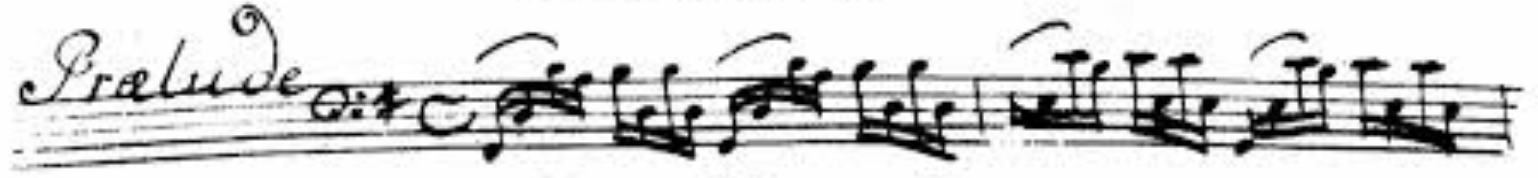

I found along the way that one really can judge a Bach recording by its cover. Here’s the cover of a recording from John Eliot Gardiner’s “Bach Cantata Pilgrimage”, a quality series of recordings of all the sacred cantatas that makes them sound fresh and new instead of fossilized:

If it looks like a National Geographic cover, that’s because they got a National Geographic photographer to make these inspiring humanist cover photos for the whole series of albums.

Meanwhile, this album cover is a warning that you’re going to have uninspired recordings shoveled at you:

Ugh. Finally, here’s the cover of an album that’s seriously called “Classical music for read a books”, performed by “Sweet reading music”:

Given the level of effort there, you might be able to guess what that album contains: recordings of MIDIs.

Good series of recordings

I found the cover images on Spotify to be important not just as an estimator of quality, but also because the easiest way to tell when a track is part of a series of related recordings is from the cover art.

After listening to enough recordings, here are the series I ended up choosing most of the time they were options:

- Anything with Yo-Yo Ma on cello

- Glenn Gould’s 1980 piano recordings

- John Eliot Gardiner / Monteverdi Choir / English Baroque Soloists, in their “Bach Cantata Pilgrimage”

- Masaaki Suzuki and Bach Collegium Japan, also performing cantatas

- Kevin Bowyer on organ with Det Fynske Kammerkor

- Simon Preston on organ, on recordings that aren’t too ravaged by time

Besides the fact that I often preferred these performers, I looked for variety when possible. Because Bach’s music is adaptable to so many instruments, I sometimes preferred performances that increased the variety of instruments, such as organ preludes featuring a trumpet, or Chris Thile playing fugues on the banjo.

I could have used Helmuth Rilling’s recordings of all the chorales (BWV 250-438). Helmuth Rilling’s ensemble is competent but unexciting, though, so I included non-Rilling recordings at many opportunities, even ones whose quality might be controversial.

Similarly, even though Gardiner and Suzuki produced excellent recordings of all the sacred cantatas, I frequently found recordings by someone else that would compare, so in those cases I tended to favor non-Gardiner, non-Suzuki recordings to increase the variety.

*

I’ve been saying this is a playlist of all-with-an-asterisk Bach pieces. What’s with the asterisk?

The problem is just that “all Bach pieces” is a bit hard to define. My intent is to have one recording of every authentic Bach piece from BWV 1 to 1128.

Some Bach pieces have been lost to history. Those tend not to have BWV numbers, at least, except in the BWV Anhang (the appendix). But among the ones that do have BWV numbers:

BWV 216 only survives in a fragmentary state, and no recordings of it are available on Spotify.

BWV 224 is extremely fragmentary — only 30 measures survive — and as far as I can tell, those 30 measures have not been recorded anywhere.

A number of chorales in BWV 250-438 correspond to organ arrangements in BWV 599-644, and sometimes their best recordings put them together in the same track.

Occasional recordings include pieces that aren’t in the BWV list. You’ll find a canon labeled “BWV deest” between BWV 1077 and BWV 1078 in the list, for example, because the performers think it goes there.

Many pieces with BWV numbers have since been deemed to be spurious — that is, not by Bach at all.

BWV 216 and 224 are missing from the list out of necessity. I skipped the BWV numbers that are considered spurious by broad consensus — okay, fine, considered spurious by bach-cantatas.com and Wikipedia. If we know which other composer actually wrote a piece, I definitely left it out. In cases of doubt, I left pieces in the list.

I tried to avoid duplicating tracks, so some pieces in BWV 250-438 actually appear somewhere in BWV 599-644 in the order of the list.

So that’s what the asterisk is about. When I last checked, the list contains 1075 unique, non-spurious Bach pieces (and probably some spurious ones that we just don’t know are spurious yet). And that’s as close to “all” of them as you can get on Spotify.

To understand the list better, you can look at the Google spreadsheet I used for keeping track of the pieces I was adding, which shows the complete list of pieces and performers. The gray rows are the numbers left out because they’re spurious, and the purple rows are duplicates of a recording that appears somewhere else in the list.

What did I find when I listened to all of Bach?

I’ll be posting some follow-ups about the recordings that were particularly interesting, and the ones that are simply too good to not listen to. For now, follow the lists and enjoy the music.

I’ll end with a quote from an unlikely music critic, a great author who would have been overjoyed if he had lived to see the Internet become the world’s greatest music library:

“Beethoven tells you what it’s like to be Beethoven and Mozart tells you what it’s like to be human. Bach tells you what it’s like to be the universe.”

— Douglas Adams